Melanie Spiller and Coloratura Consulting

Copyright 2020 Melanie Spiller. All rights reserved.

Verbs

Melanie Spiller and Coloratura Consulting

A verb is an essential part of any sentence. In fact, you can’t have a sentence without one, and a single verb

can be the whole sentence. It’s entirely possible to say “Go” or “Eat” and call it a day, sentence-wise.

A verb describes the action or existence discussed in a sentence. The verb also tells you when the event

happened because verbs indicate tense (present, past, future, and subjunctive). And verbs provide

information about whether the noun is plural or singular. A verb can be all there is in an imperative sentence,

like “Go” and “Eat” or even “Go eat.” In these little sentences, the implied pronoun is “you,” as in “You go,”

or “You go eat.”

Verbs provide all this nifty information by being conjugated, which just means that their endings or vowels

change a little bit to accommodate the noun or pronoun, to show tense, and to contribute information about

whether the noun in question is singular or plural. (There are lots of plural nouns, like fish and sheep, where

you need the verb to tell you whether it’s one fish or several fish.)

Whether you’ve done it in a language class or not, you’ve been conjugating verbs all your speaking life. You

instinctively form the correct version of your verbs at least most of the time because you were taught to do it,

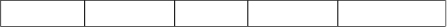

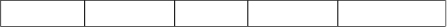

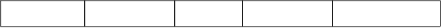

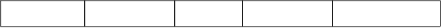

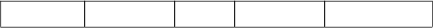

by imitation and in the classroom. Here’s how conjugating looks in a table:

To conjugate, you take the pronoun and change the verb to accommodate the form required. When your

sentence doesn’t have a pronoun, you do pretty much the same thing to the noun; you substitute “he/she/it”

for most nouns with articles, like “the boy drags the teddy bear” or the plural “they,” like “boats drag water

skiers,” for nouns without articles. (Articles are the words “a,” “an,” and “the.”)

Note that the most of the forms of the verb in the table are all the same, except present tense “he/she/it” and

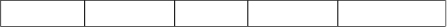

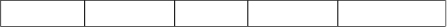

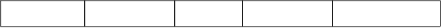

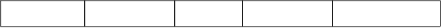

past tense. Also note that the past tense for drag is NOT drug. See? It’s easy. Here’s another one, an irregular

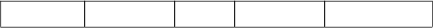

one, to look at.

“Think” is an irregular verb because the word changes so completely in the past tense. But it’s still not hard.

You add that same “s” ending for he/she/it like you did for drag, and the past tense form is quite changed but

the same form the whole the way.

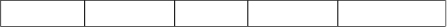

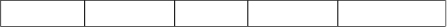

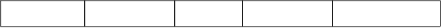

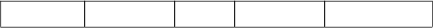

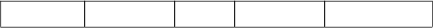

Here’s the most irregular verb of all, and the most frequently used verb, “to be.”

This verb is really different from most other verbs because you don’t find the infinitive version (the part with

“to” in it, like “to drag” or “to think”) in any of the conjugated forms. But its basic purpose is to describe a

state of being (doesn’t that sound terribly Californian and New Agey?), and that’s why it’s called “to be”

even though there’s no “be” in the conjugated form. Even though it’s extremely irregular (compared to the

others), conjugating “to be” is not that hard—in the present and past tenses, only the forms for “I’ and

“he/she/it” are different. Once you figure out which tense you’re in, most of the forms are the same all the

way down the list.

Now let’s look at tenses. Tense in a grammatical sense has to do with when something happened. When

some editor says you’ve mixed tenses, it’s because you’ve got something happening in the past and

something else happening in the present, most likely. That kind of thing really confounds non-native English

speakers, and it’s confusing to native speakers too, so it’s a good idea to be careful.

The present tense is the easiest form. You are writing about something that is happening right now. So if you

tell the tale of the sporting event of the century, unless you’re the announcer providing blow-by-blow, you

won’t want present tense. The event already happened by the time you get to tell the tale, so use past tense.

The one exception is when talking about literary plots, be they movies, books, or theater spectacles. For

some reason, it has become appropriate to retell these plots as though they were happening right now, even

though you already read or saw the story. I didn’t make this rule—or I’d change it. But anyway, use present

tense when providing instructions (click OK, go to the third floor, make a new page, etc.).

Past tense is when something already happened. I already typed that sentence, so I can say “I typed” rather

than “I type.” In the case of most regular and many irregular verbs, the form of the verb is the same for all

pronouns in the past tense. Use past tense to tell someone what you already experienced, whether it is the

development of an application, a train wreck, or lunch. Regular verbs get an “ed” ending and irregular verbs

have interior letters (like “think” to “thought” or “break” to “broke”) or ending letters changed (like “says”

to “said”).

The future tense is when something hasn’t happened yet. Most of the time, this form involves the “helping”

verb “will.” Use this form when you’re talking about something happening in the future. Do not use this

form when you’re talking about actions you want your readers to take. (“Clicking OK will make the changes

take effect.” Well yes, it will make the changes take effect, but that’s not an instruction.) Do use this form

when you only want to describe the effect one thing has on another but you don’t want the reader to take any

action. (“Clicking OK will have dire consequences if you don’t save your changes first.” This is a warning,

not an instruction, so it’s okay.)

I’ve talked about subjunctive in a previous blog (called Subjunctive Renaissance), and briefly, all it does is

express the condition of the unreal. You use subjunctive if you wish something were true or if it might have

been true in different circumstances, like “if I were queen,” or “if only there were four of them.” “If” comes

up a lot in subjunctive sentences.

There’s another form of verbs, called a participle. These involve “helping” verbs, which are just second

verbs that “help” the main verb by indicating time or intention. Helping verbs include may, have, could, and

should and all their forms (have, had, has, may, might, and so on). You use a participle to place action in the

recent past (“I have had lunch”) or to show that there was causality (“he had his hair cut”). There are past

participles, present perfect participles and all sorts of other flavors, and I’ll cover these more fully in another

blog.

Gerunds are a form of verb that ends in “ing.” Gerunds impart present tense information and almost always

require the presence of another verb, although the second verb isn’t necessarily a “helping” verb. Consider

these sentences:

He was running away.

He ran away.

The frog is singing.

The frog sings.

You can see that the meaning is changed—it’s a less active sentence using the gerund form. That’s not

always a bad thing; sometimes you need to get some distance between the action and the telling about it.

There’s lots more to tell about verbs, and that’ll happen in a later blog or two. For now, it’s enough to

admonish you to be aware of which words are verbs and what tense they’re in.

Pronoun

Present

Past

Future

Subjunctive

I

drag

dragged

will drag

would drag

you

drag

dragged

will drag

would drag

he/she/it

drags

dragged

will drag

would drag

we

drag

dragged

will drag

would drag

you (all)

drag

dragged

will drag

would drag

they

drag

dragged

will drag

would drag

Pronoun

Present

Past

Future

Subjunctive

I

think

thought

will think

would think

you

think

thought

will think

would think

he/she/it

thinks

thought

will think

would think

we

think

thought

will think

would think

you (all)

think

thought

will think

would think

they

think

thought

will think

would think

Pronoun

Present

Past

Future

Subjunctive

I

am

was

will be

were

you

are

were

will be

were

he/she/it

is

was

will be

were

we

are

were

will be

were

you (all)

are

were

will be

were

they

are

were

will be

were